Have journalists failed our news industry? JioStar's Uday Shankar shares his views on the business of journalism

Shankar, in an honest diagnosis, said the worst thing to have happened in the news media was advertising becoming the dominant revenue contributor, making publishers undervalue their audiences.

Uday Shankar, vice chair of the $8.5 billion entertainment, sports and streaming media conglomerate, JioStar, explained why he believes India’s news industry has been in a death spiral for the past two decades: lack of innovation, talent and capital, leading to cost cutting, and resulting in a gradual hollowing out.

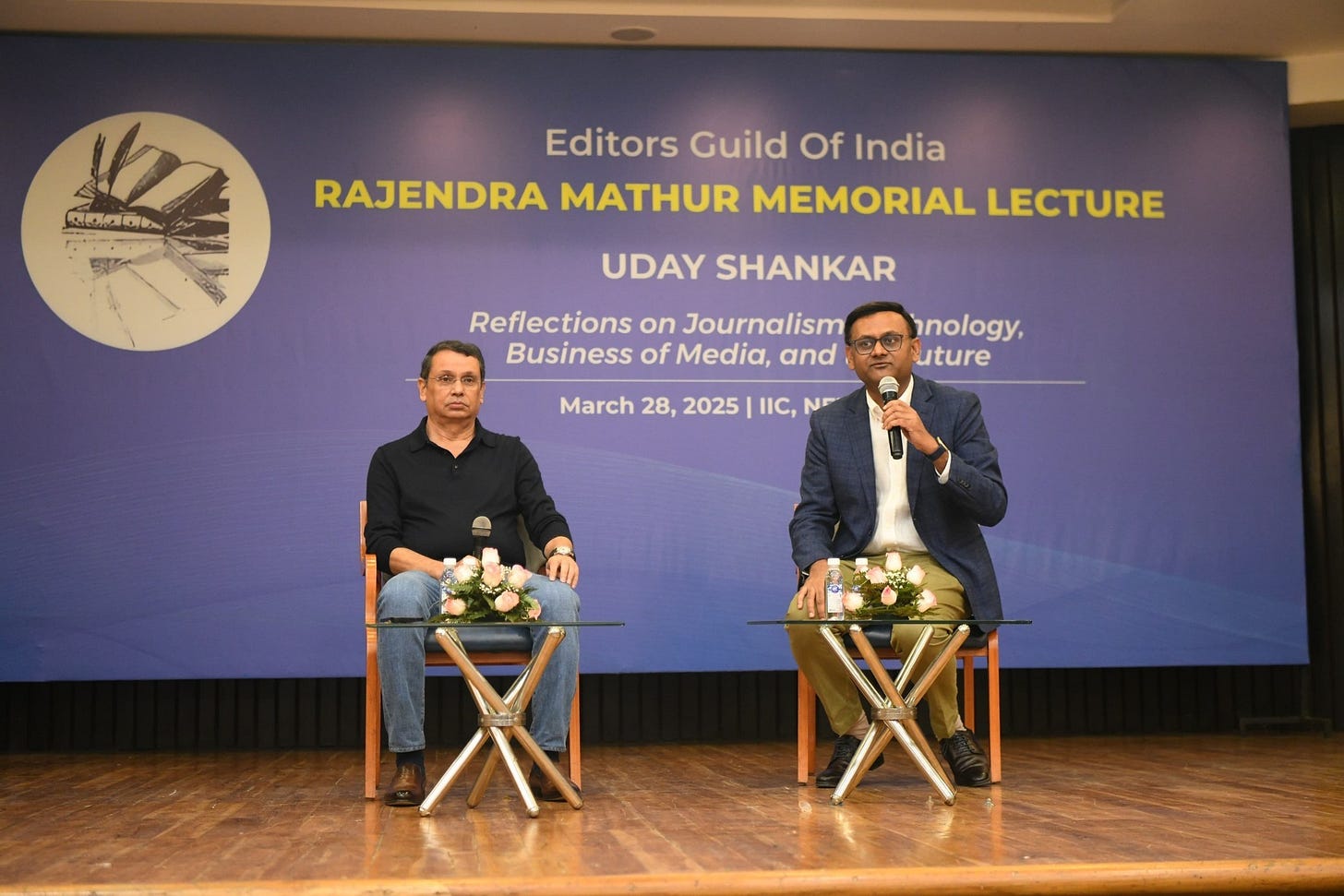

Here’s a breakdown of the key aspects of Shankar’s speech delivered at the Rajendra Mathur Memorial Lecture organised by the Editor’s Guild of India in New Delhi on March 28, 2025.

First, he presented six factors for his hypothesis:

Wither thy product: Journalists are largely to blame for the institutional decline of the mainstream media because they failed to engage with the business/commercial of their respective organisations. They have not led innovation and experimented enough with new product ideas and formats.

A paradoxical attitude: Many journalists want to be paid a lot of money, but they feel that if they participate in efforts to help their company make money, then they’re somehow betraying the ‘cause of journalism’. The old ‘Church and State’ separation of the editorial and commercial sides within a news organisation might have been taken too far by editorial leaders abdicating their responsibilities (or perhaps being kept away by owners and managers). Ultimately, journalists not having their ears to the ground and anticipating needs of their audience diluted their output.

Toxic motives: The most damaging thing that came out of the dysfunction between the relationships of journalists and business managers in news companies was that advertising became the dominant source of revenue. “Advertisers don’t care about quality (of the product), they care about reach.” (As an aside: “The worst quality of managers exists in Indian media, whose only qualification seems to be ignorance.” More on the talent crisis below).

A race to the bottom: news organisations started creating content that could deliver advertisers more reach, normalising sensational, tabloid-style journalism and playing to the lowest common denominator. There was no attempt to build a direct relationship with the reader or viewer and unique brand voice to stand apart from the noise.

A talent crisis: the media was a big beneficiary of India being a small, underdeveloped economy during the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s because a lot of top talent from its universities came into journalism. There were hardly any opportunities in the private sector and journalism was seen as a viable, even attractive profession. Post the ‘00s, ‘10s the news industry had to compete with greener pastures, who are able to lure away top talent at top salaries. The best of today’s youth are not interested in becoming journalists or media professionals.

Capital capitulation: India’s news media is among the most undercapitalised in the world. This is because too few news outlets have a deep enough direct relationship with their audience that enables multiple revenue streams. There is barely any subscription or reader revenue to speak of when compared to the costs of running news operations. What’s left is big corporate capital, which has led to the acquisition of independent news companies by larger organisations (Shankar duly acknowledges that there’s “such a direct conflict of interest that its hard to maintain Chinese walls.” In his current role, he is partnering with Reliance Industries Ltd that owns one of India’s largest news media companies - more below).

Next, he offered some solutions for journalism in India:

Raison d'etre: The change (product innovation) can only come from journalists. “Journalists are not a cost centre—something I used to hear a lot and which used to annoy me to no end. Journalists are the ones who create the product. Journalists are the reason people look at a screen or a newspaper or magazine.” They need to lead innovation and keep the news relevant.

Money matters: Product innovation comes first. But there needs to be innovation in monetisation models too. Monetisation models need to evolve in such a way that they do not damage the direct relationship that news brands cultivate.

Hungry Indians: The good news is that there is significant appetite among audiences with more time being spent on content consumption than nearly anywhere else in the world. Demographics are in the media’s favour, with over 65% of India’s population being under 35 years old. However, newsrooms and media organisations need to appeal with more vigour and vitality to younger demographics.

Holy cows and platitudes: Shankar admitted that in the highly polarised and corporatised news environment, journalists were operating under constraints. “We know that we can’t report on everything because some of that is too uncomfortable for a lot of people. But what we report must be credible.” The most premium currency for media can be credibility. (Shankar fell back on that oft cited example of success in the news media—NYTimes— to nudge media executives to seek inspiration and maintain credibility in all that they do. He referred to NYT’s Wirecutter product reviews, which makes money through affiliate links, but has kept its trust with its audience in place.).

Who is Uday Shankar?

Uday Shankar began his journey as a trainee with The Times of India in its Patna bureau in the late 1980s. He became a news producer with ZeeNews in 1995. Today he helms one of Asia’s modern media enterprises, JioStar. His main career success came when he launched and ran Aaj Tak, India’s first 24-hour Hindi news channel in the early ‘00s and later when he worked for the Murdoch clan as the CEO of Star India, making it the country’s top entertainment and sports broadcaster. Subsequently, Shankar saw the streaming future early enough to build Hotstar within the Star group. He scaled it rapidly for adoption on mobile and pioneered live sports streaming in South Asia. He aggressively promoted cricket (esp. the Indian Premier League), kabaddi and other sports. He was made head of Murdoch’s entire electronic media footprint in the Asia Pacific. Meanwhile, 21st Century Fox, the parent company that owned many of Rupert Murdoch’s assets in Asia, was sold to The Walt Disney Company. This meant that Shankar became President for The Walt Disney Company’s Asia Pacific region. However, with the fissures in the Murdoch family getting deeper, Shankar quit Bob Iger’s Disney Co. and joined hands with his long time collaborator James Murdoch to form Bodhi Tree Systems, an investment platform with a slew of backers such as Comcast, NBC and the Qatar Investment Authority. Industry watchers say that his swashbuckling/intrepreneurial style that worked beautifully in the Murdochian system, ran into corporate red tape at Disney Co. Bodhi Tree Systems invested $528 million into Viacom18 (a Reliance Industries Ltd-Paramount joint venture), with Reliance Industries buying out Paramount and eventually combining with The Walt Disney Company to form Disney Star India, that’s been renamed JioStar, a fundamentally digital venture, but one that owns over a hundred TV channels.

Side note: The influence and control of Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL) and its promoter family—Mukesh and Nita Ambani and their children—across this spectrum of activity is significant. RIL is the majority shareholder of JioStar, with Nita Ambani as its chairperson. It also holds majority control of a related news media conglomerate—Network18 Group—which is an upstream investor company into JioStar through Viacom18. While Network18 and JioStar are legally separate entities, it is imaginable for synergies to be explored between them.

JioStar Shareholding Structure (in Nov 2024):

Reliance Industries Limited (RIL) - 16.34%

Viacom18 Media Pvt Ltd - 46.82%

The Walt Disney Company (Disney) - 36.84%

Upstream Ownership Details:

Bodhi Tree Systems: Holds a 0.011% equity stake and 17.8% of the compulsorily convertible preference shares (CCPS) in Viacom18. Upon conversion of these CCPS, Bodhi Tree Systems' stake would increase to approximately 13.08% on a fully diluted basis.

Watch the full lecture followed by Q&A. Images courtesy Editors Guild of India.

Questions, Issues and Ideas

Is Shankar being too pessimistic or is this a realistic assessment of the business of journalism in India? Has journalism not struggled the world over?

Aren’t ecosystem factors that are beyond the scope of journalists and journalism at play, which have led to the hollowing out of the news industry?

Is the news industry hollowing out? Are there companies that are doing well in India, at least financially, if not from the perspective of editorial quality? Is editorial quality a response to what audiences want and therefore addressing those needs?

What about the role of the state in driving large parts of the media into submission or politically favourable content? Is it possible to build a robust news media business in India without the support of the government of the day?

Who are some of the top news innovators and journalists that are doing work out there that are likely to see success as defined by Shankar in this lecture?

One final takeaway: Shankar was quite unforgiving in his assessment of how journalists have failed to play a leading role in reshaping the news industry, perhaps rightly so. However, he values the skills of reporters and editors immensely, having himself successfully deployed an analytical mindset and critical thinking skills in his role as a media executive.

Here’s why he feels a journalistic mindset helped him in taking his career forward in this interview with McKinsey & Co. from October 2024:

If you’re a good journalist, and a serious one, one of the things that you do very well is you look at a problem, analyze that problem, and then identify who the best people are to find an answer to that problem. And you go to them and challenge them. You try and see where they’re leading you, or where they’re not right.

That is what I have done. I focus closely on a problem, break it down into its tiniest pieces, and then sit with the best minds to see how to crack the problem. I still use what I learned from my days as a reporter and editor to push my team to get out of their comfort zone, look at a problem, analyze it, and find solutions that most people have not found.

Also, as a journalist, you look for the big, bold headlines. Nobody comes for the 18th story; people come for the first two or three stories. Similarly, if you solve a small problem or many small problems, the effort is the same as, if not more than, solving a bigger problem. It tends to exhaust the team and makes them impatient because they don’t see great results, appreciation, or value creation.

I realized that I had a choice between doing too many things or doing a few things and creating disproportionate impact. And that’s worked for me. In fact, I get very unsettled in situations where executives and my leaders start doing too many things. In all the roles that I have played in the last 15 years, the big value that I have added for my teams is to push them to do less, but with greater impact.